WELCOME

||

106

terwards. Since the 14th century, traditions slowly walked away from

liturgy, which lead to more freedom – at least from a dramaturgic

point of view. A good example for their modern perversions are our

office Christmas parties.”

(147. Annual report 2004, the Monastery Sec-

ondary School of Kremsmünster, theologian P. Klaudius Wintz).

By the way, the tradition of the Christmas tree plundering, which took

place on December 25, was as important as the tree itself. It represent-

ed “shaking off” the sins, referring to the salvation of humanity through

Jesus Christ. In the end, it was the Protestants, who lead the tradition of

our modern Christmas tree to its victory.

“Setting up a nativity scene would have been a horrific thought for

a real reformer, as Protestants considered the worship of an idol or a

physical object as a representation of a god a consternation of an in-

nocent soul. Therefore, in the middle of the 16th century, the Christ-

mas tree was introduced as an anti-Catholic counterpart to the na-

tivity scene. It was only in the 19th century, when the Christmas tree

was finally tolerated also beyond the borders of Elsass.”

(147. Annual

report 2004, the Monastery Secondary School of Kremsmünster, theolo-

gian P. Klaudius Wintz).

It still took a while though, until the custom of setting up a Christmas

tree in one’s own home became popular in Austria. Because unlike to-

day, back then pine trees were a rare commodity in Central Europe and

only the rich could afford this luxury.

Starting from the middle of the 19th century, pine plantations were

established, which enabled more families to buy their own Christmas

tree. At the same time, it started to become common to decorate the

tree with candles, which was important to the Catholic belief in order

to be able to tolerate the tradition as these candles were meant to rep-

resent the light that was brought into this world through Jesus Christ.

From the cradle to the nativity scene

In Tyrol, a Christmas without nativity scene is totally inconceivable.

However, it was not here in Austria, where the nativity scene was in-

vented. The art of crib-making leads

back to two customs:

Firstly, the custom of cradling, which

developed in the 13th century in nun-

neries. Every year on Christmas Day,

nuns used to cradle a doll, symbolising

baby Jesus. In the course of time, the

making of baby Jesus figures out of wax

or wood became common, which were

placed in beautifully decorated cribs.

Starting from the end of the 16th cen-

tury, those figures were set up in peo-

ple’s living rooms as a popular Christ-

mas decoration. Nativity scenes as we

know them today didn’t exist back then.

As a result, baby cradling developed as a tradition among the peo-

ple: It was mostly women in need, who during Advent time used to

take their own child or a doll with a cradle from house to house. The

cradle was then placed on the table, and while the people were pray-

ing together, the woman was cradling the baby. In return, she received

groceries and sometimes a little bit of money. In Tyrol, this custom

was practiced until far into the 20th century, but it slowly faded away.

In the 1960s, people tried to revive the tradition without success. Even

today, there is still a few, who try to bring baby cradling back to life.

The second custom, which influenced the development of nativity

scenes, were the Christmas games.

In very early times, those games were held in churches to illustrate

the birth of baby Jesus for people who couldn’t read. This is how the

nativity scenes finally evolved.

In the Museum of Tyrolean Regional Heritage, an extensive collec-

tion of nativity scenes from the Alpine regions with huge grips of 1 m

length can be admired from December until January. Crib exhibitions

are very popular in Austria – not only in public places but also in pri-

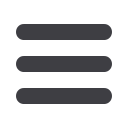

Eine weitere traditionelle Axamer Fasnachtsfigur ist der Flitscheler, er

symbolisiert Fruchtbarkeit. Auf der Jacke eines alten Anzugs, die verkehrt

herum getragen wird, werden zusammengeknotete, getrocknete Blätter

der Maiskolbenenden, die sogenannten „Flitschen“, aufgenäht. //

Another characteristic figure of Axams is the “Flitscheler”. He stands for fertility.

The jacket of an old suit is worn inside out and decorated with the dried

leaves of corncobs - the so-called “Flitschen”.

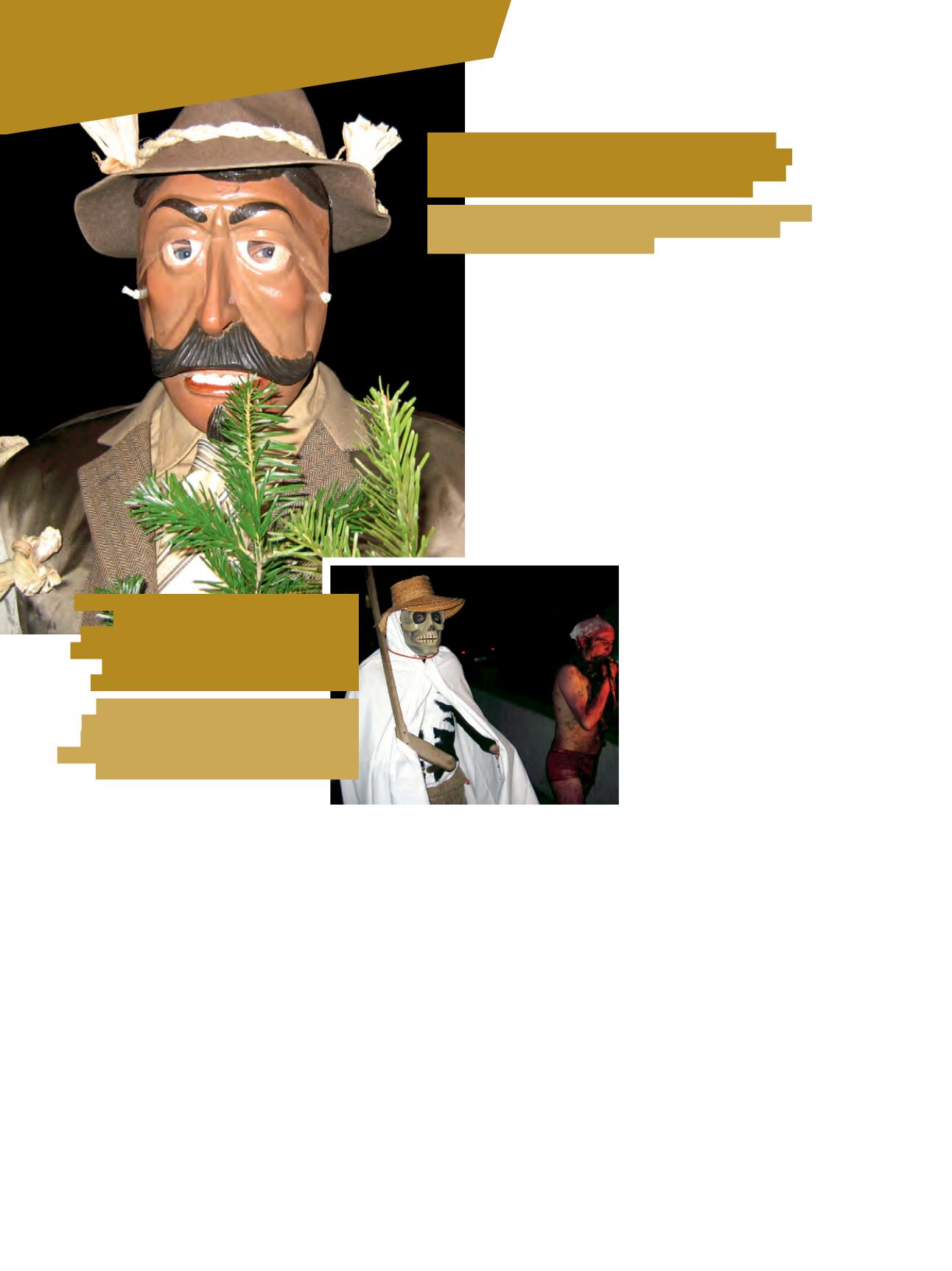

Ein Bestandteil des Axamer Fastnachtsbrauchtums sind

die Bluatigen: Mit Tierblut beschmiert, im Mund

Erdäpfelzähne, fauchend und furchteinflößende Laute

von sich gebend schleichen sie umher ... Und ihnen stets

voran geht der „Tod“ – mit weißem Umhang, einer

Totenkopfmaske und einer Sense auf der Schulter. //

The “Bluatigen” (the bleeding) are an integral part of

Axams’ carnival: They sneak around covered in animal’s

blood, baring their huge potato teeth and making scary

sounds. The “death” always walks ahead of them – in a white

coat, a skull mask and with a scythe on his shoulder.